Wearables fail in the real world when the skin gets hot, wet, and irritated, even if the electronics work. I have seen good designs lose user trust because the material choice was made too late.

To balance breathability and stickiness, I start from the skin microclimate, then I pick a silicone system that controls gas and moisture transport, and I match it with an adhesion strategy that survives sweat, oil, and repeated wear.

I used to think I could “fix” comfort by only changing adhesive strength. Then I learned that comfort is a system problem. It starts at the skin, then it moves through the silicone, then it ends at the interface.

What is the skin microclimate and why does it decide whether a wearable feels “breathable”?

Hot spots and sweat build up under a wearable because the skin is alive and always changing. If the surface is sealed, the trapped heat and moisture can rise fast. Then the user feels itching, slipping, and even pain. I have seen users blame the device, but the real issue was the microclimate.

The skin microclimate is the thin layer of heat, moisture, and skin oil trapped between the device and the skin, and it controls comfort, slip, and irritation.

What I look at first in the microclimate

When I review a wearable concept, I ask simple questions before I talk about chemistry.

- Where is it worn, and how much does that area sweat?

- Is there hair, motion, or bending that pumps moisture in and out?

- Is the device worn for 1 hour, 8 hours, or all day and night?

- Does the device need sealing against water from outside?

A simple way I map risk early

I often use a quick matrix so the team can see the trade-offs without a long meeting.

| Wear condition | Sweat level | Motion level | Microclimate risk | Typical failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office, short wear | Low | Low | Low | Minor marks |

| Daily use, long wear | Medium | Medium | Medium | Slip, edge lift |

| Sports, long wear | High | High | High | Rash, strong odor, skin damage |

If the risk is high, I do not start with “stronger adhesive.” I start with transport, softness, and interface design. Then adhesion becomes easier to control.

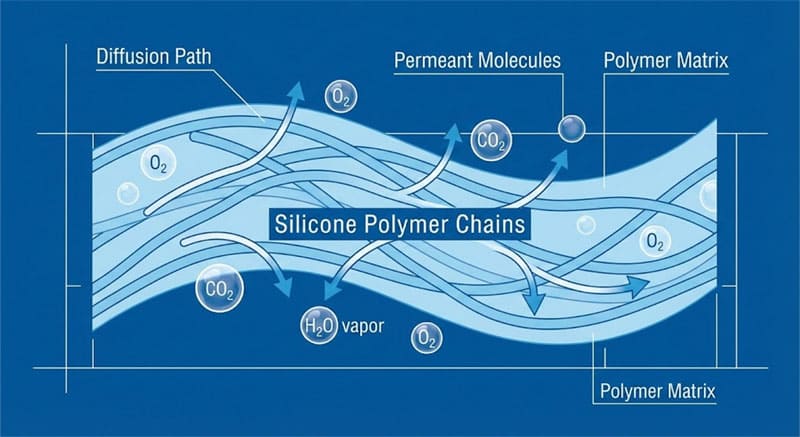

Which silicone formulation choices change gas permeability in a wearable?

Many people think silicone is always breathable. That is not true in practice. Silicone has good gas permeability compared with many plastics, but the real result depends on the full formulation and the thickness. If the part is thick, it can still feel sealed. If the formulation is loaded with fillers, permeability can drop. If the surface is treated or coated, transport can change again.

Gas permeability in silicone is controlled by polymer structure, filler loading, crosslink density, and thickness, so formulation and geometry must be selected together.

What I compare when I choose a base silicone system

I usually compare candidates on a short list. I keep the language simple so it can work across design, materials, and QA.

| Choice factor | If I increase it | What I often see | What can go wrong |

|---|---|---|---|

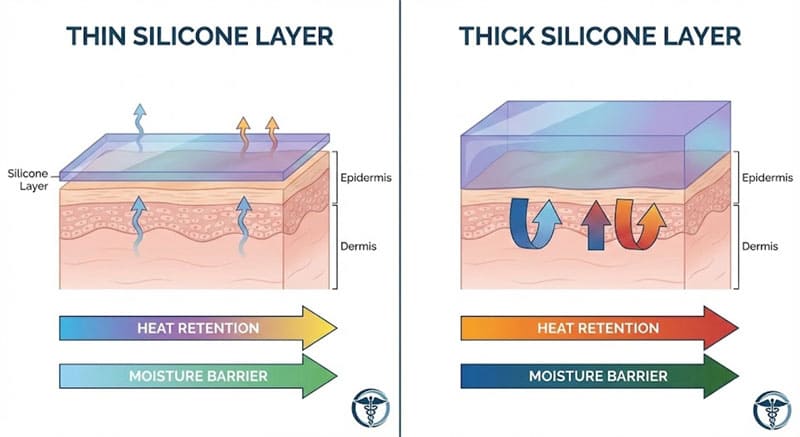

| Thickness | Higher barrier | Better sealing feel | Heat and sweat build up |

| Filler loading | Lower permeability | Better strength, lower cost | Less “breathable” feel |

| Crosslink density | Lower diffusion | Better set resistance | Stiffer feel, less comfort |

| Softness (lower modulus) | Better conformity | Better skin contact | More creep, edge lift |

A practical rule I use

If the wearable must be worn for long hours, I push for a thinner silicone layer where possible, but I support it with structure. I would rather use design ribs and smart geometry than make the whole part thick. Thickness is the fastest way to kill breathability.

Which adhesion system should I choose for wearables?

Adhesion is where most wearable teams feel stuck. They want a bond that is strong, but they also want clean removal. They want it to work in sweat, but they also want low irritation. These are real conflicts, so I do not pretend there is one perfect answer.

I choose the adhesion system based on wear time, removal frequency, and skin sensitivity, then I tune peel and shear performance for sweat and motion instead of only chasing higher tack.

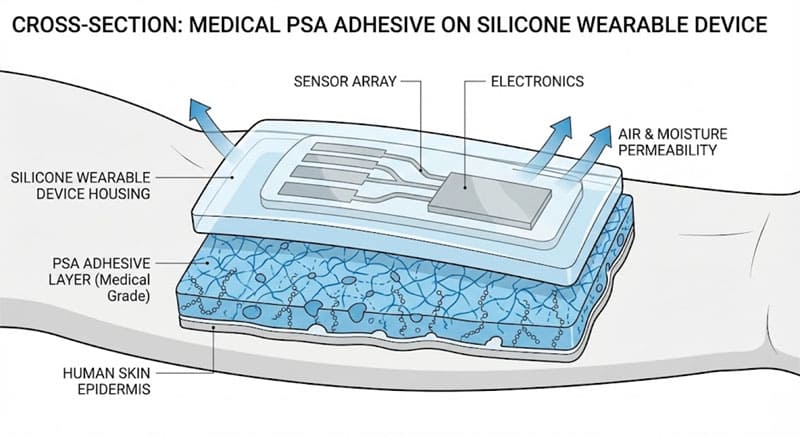

Option 1: Medical pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA)

Medical PSAs can be reliable and predictable if the design is right.

- Best for: single-use patches, long wear, controlled removal

- What I like: stable performance, known test methods, supply chain maturity

- Risk: skin stripping if peel is too high, and residue if the system is not matched

Option 2: Surface treatment to improve bonding

Surface treatment can help when silicone needs to bond to another layer, or when a coating must stick.

- Best for: bonding silicone to films, improving coating adhesion, process control

- What I like: it can raise bond strength without changing bulk silicone

- Risk: treatment aging, uneven treatment, and hard-to-debug field failures

Option 3: Reusable tack or “re-stick” systems

Reusable tack looks attractive for consumer wearables, but it needs honest testing.

- Best for: devices that must be removed and put back many times

- What I like: user-friendly behavior when it works

- Risk: sweat and skin oil contamination, fast drop in tack, and “dirty feel”

A simple decision table I use

| User behavior | My default direction |

|---|---|

| Worn once, then disposed | Medical PSA with skin-safe peel targets |

| Worn all day, removed at night | Medical PSA or hybrid design with controlled peel |

| Removed many times per day | Reusable tack only if contamination tests pass |

| Very sensitive skin target | Lower peel, larger area, softer silicone support |

I also remind myself that “strong” is not always good. Strong can mean skin damage. I aim for stable, predictable removal. That often wins user trust.

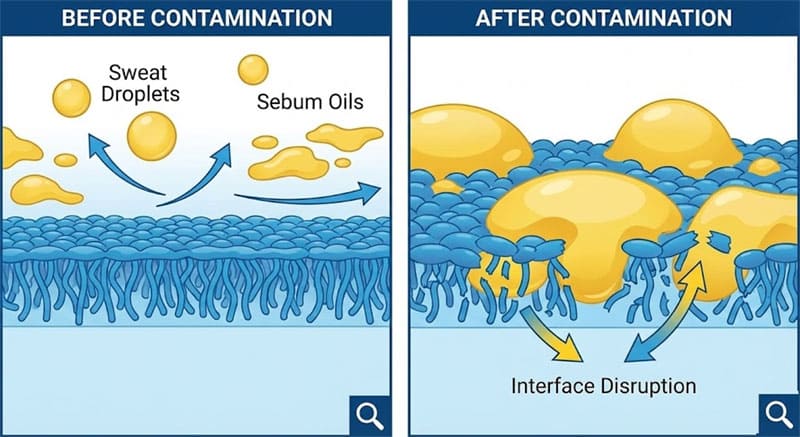

How do sweat and skin oil change silicone and adhesion over time?

Sweat is water plus salts. Skin oil is a mix of lipids. Together they can change friction, soften some layers, and reduce adhesion. Even when silicone itself is chemically stable, the interface can still fail. I have seen a wearable pass a dry lab test and fail fast in real use because the interface became slippery.

Sweat and skin oil mainly attack the interface by changing friction and contaminating adhesives, so I test with realistic humidity, salt, and oil exposure instead of dry conditions only.

What failure modes I watch for

- Edge lift after sweating, even when center contact looks fine

- Sliding during motion because the skin surface becomes lubricated

- Adhesive “whitening” or softening after humidity soak

- Odor build-up because the area stays wet and warm

How I reduce these risks with design, not only chemistry

- I use rounded edges and controlled edge thickness so peel forces stay low.

- I avoid sharp corners that concentrate stress during bending.

- I plan vent paths and micro-texture when it fits the product.

- I keep the contact area large enough so the load is shared.

When I do these steps, the adhesive choice becomes less extreme. I do not need to chase very high tack, so irritation risk goes down.

How do I design for long-wear comfort, and what human factors matter most?

Comfort is not only softness. Comfort is also heat feel, moisture feel, and the way the device moves with the body. I learned this from user feedback that sounded “emotional,” but it was actually physical. People said the wearable felt “stuffy” or “tight.” That usually meant the device trapped heat, or it pulled the skin during motion.

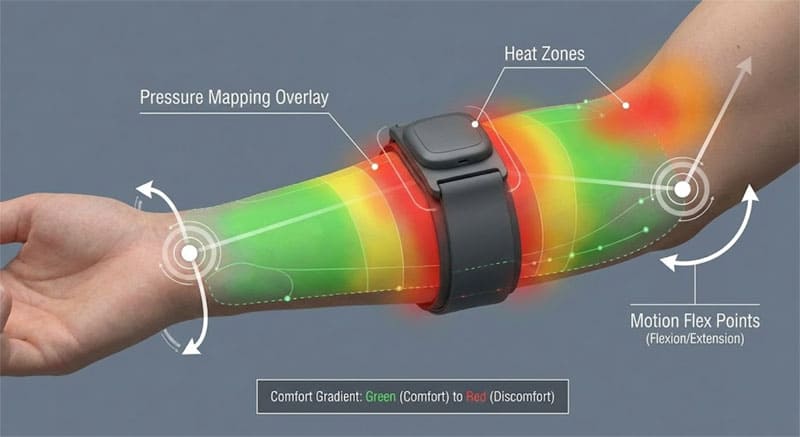

Long-wear comfort depends on thermal and moisture management, low skin stress during motion, and a geometry that avoids pressure points, so I treat the silicone part as a human factors component.

Human factors checks I run

- Pressure mapping: I look for small high-pressure zones near edges.

- Motion check: I bend and twist the device in the real wear location.

- Removal behavior: I watch how users peel it off, not how I peel it off.

- Skin mark check: I check redness after 30 minutes, then after longer wear.

My comfort design habits

I try to keep the wearable compliant in the direction of body motion. I also reduce stiffness gradients. If one area is stiff and the next is soft, the skin sees stress at the boundary. I also avoid thick “lips” that act like a seal. If I need sealing, I do it in targeted zones, not across the whole area.

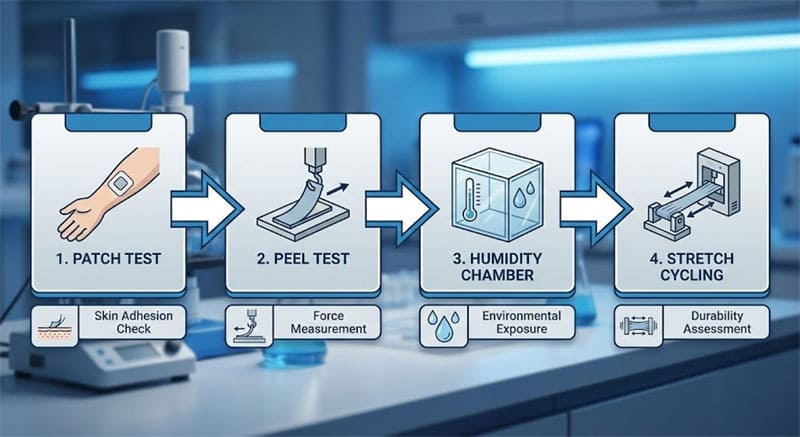

Which validation methods best prove breathability and adhesion for wearable silicone designs?

If the product goal is real-world wear, then the test plan must look like real-world wear. I still use standard tests, but I do not stop there. I build a test stack that connects material data to user outcomes. That helps me explain trade-offs to the team and also helps me avoid surprises.

I validate silicone wearables with a mix of patch testing, peel and shear under humidity, and stretch cycling with temperature and sweat exposure, because single-condition tests miss the interface failures.

1) Patch testing (skin compatibility)

I use patch testing to check irritation risk. I also use it to compare design variants. Even small geometry changes can change redness. I track time, location, and removal method.

2) Peel strength and repeat removal

Peel strength is not just one number. I measure it after humidity soak and after sweat exposure. I also measure it after repeated apply-remove cycles if the product is reusable. I log residue and user feel, not only force.

3) Stretch cycling and motion simulation

Wearables bend. I run stretch cycles that match the expected use. I also cycle at temperature and humidity because silicone softness and adhesive behavior can change with heat.

4) Temperature and humidity stress

I run hot-humid storage and then test adhesion again. I do this because some interface treatments and adhesive layers can change over time. Aging can be silent until the product is shipped.

A basic validation map I like

| Test | What it answers | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Patch test | Will skin react? | Prevents user drop-off |

| Peel after humidity | Will it lift? | Real sweat behavior |

| Shear under load | Will it slide? | Motion stability |

| Stretch cycling | Will edges fail? | Long-term wear |

| Aging | Will it change later? | Shelf life confidence |

Conclusion

I balance gas permeability and skin adhesion by starting from the skin microclimate, then choosing silicone and geometry together, then validating the interface under sweat, heat, and motion.