Silicone is widely regarded as a thermally stable and non-degrading material, largely because of its strong Si-O backbone. While the chemistry is fundamentally sound, this belief often oversimplifies how silicone actually behaves in real industrial environments.

In practice, silicone stability is not a material constant. It is a process-dependent variable—one that is frequently mismanaged when teams equate “no visible damage” with “no functional degradation.”

From a manufacturing perspective, silicone does not fail dramatically. It fails quietly, through changes in physical properties driven by thermal history, residual volatiles, and post-curing discipline.

Why Silicone Appears “Thermally Indifferent”

Compared to organic elastomers such as EPDM or nitrile rubber, silicone does not char, melt, or liquefy when exposed to elevated temperatures. This visual resilience leads to a common engineering assumption:

If the part hasn’t deformed, it hasn’t degraded.

This assumption is incorrect.

How Heat Actually Degrades Silicone

In long-term thermal exposure, silicone degradation rarely involves chain scission. Instead, oxygen attacks side methyl groups, leading to unintended increases in crosslink density.

- The polymer backbone remains intact

- The part retains its shape

- Mechanical compliance quietly disappears

A gasket may look unchanged after thousands of hours at temperature, yet lose its ability to seal due to reduced elastic recovery.

Silicone Degradation Mechanism: Crosslink Density Drift

Unlike organic rubbers, silicone degradation manifests as a shift in physical behavior, not material collapse.

Key effects observed in production testing include:

- Increased hardness

- Reduced rebound force

- Loss of vibration damping

- Elevated compression set

These effects are gradual, cumulative, and often missed until field failure occurs.

The Role of Manufacturing Process in Silicone Stability

Unreacted Volatiles: The Hidden Risk

One of the most overlooked contributors to silicone instability is the presence of residual low-molecular-weight siloxanes left behind after molding.

If these volatiles are not removed through adequate post-curing, they remain trapped inside the elastomer matrix.

In high-temperature, sealed environments—such as automotive sensors or medical enclosures—this creates a pathway for long-term failure.

Depolymerization and the “Back-Biting” Effect

Under heat and moisture, residual siloxanes can initiate depolymerization, often referred to as back-biting.

Instead of breaking apart visibly, the polymer chains:

- Fold back on themselves

- Re-form cyclic siloxanes

- Gradually transition toward a fluid-like state

This phenomenon is not a failure of silicone as a material—it is a failure of process control, specifically insufficient post-curing.

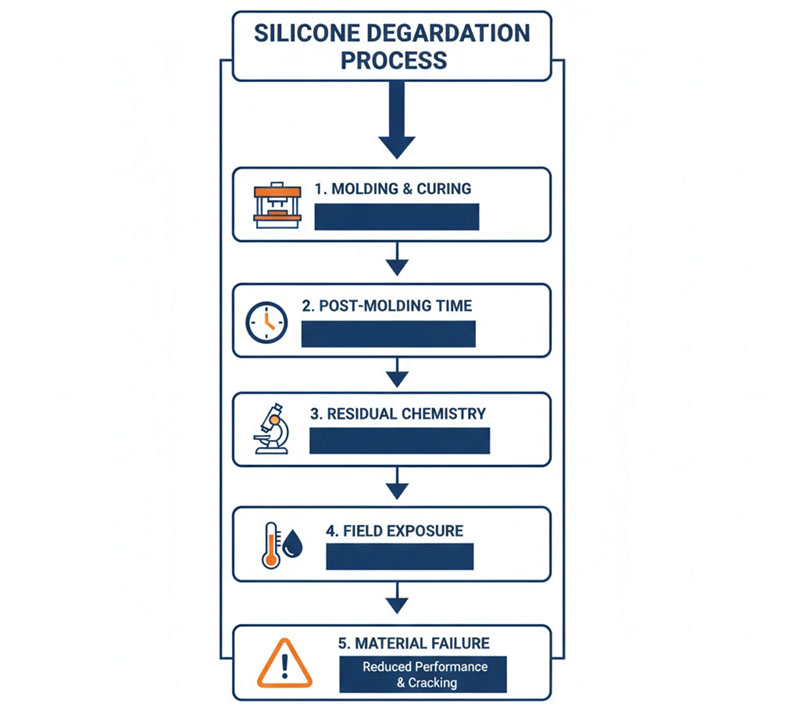

Typical Failure Chain

- Initial molding: Part appears complete and dimensionally stable

- Post-cure shortened or skipped: To save time or cost

- Residual chemistry remains active: Volatiles not driven off

- Field exposure: Heat + moisture activate depolymerization

- Delayed failure: Often 12–24 months into service

How to Detect Silicone Degradation Before Failure

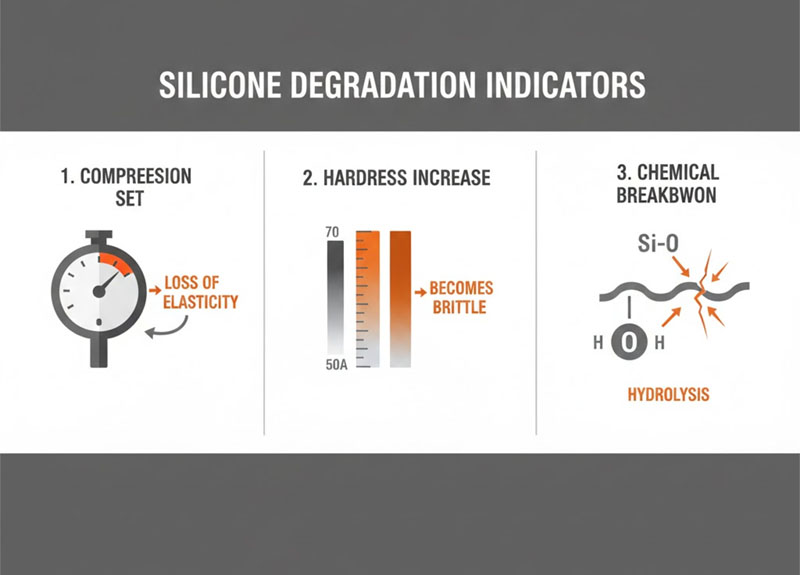

When evaluating long-term silicone performance, three indicators reliably signal that the material is approaching its functional limits.

1. Compression Set Increase

The most common silicone failure mode is not cracking—it is loss of recovery force.

- Gaskets stop pushing back

- Seals lose contact pressure

- Leakage occurs without visible damage

Despite its importance, compression set is often underemphasized in initial specifications.

2. Durometer Creep

A silicone part molded at 50 Shore A may gradually harden to 60–70 Shore A after prolonged heat exposure.

As hardness increases:

- Damping performance decreases

- Vibration isolation is compromised

- Assembly forces rise

3. Hydrolytic Stability Limits

In steam-rich or high-humidity environments, the Si-O-Si backbone can be susceptible to hydrolytic cleavage unless the formulation is specifically designed to resist it.

Do Silicone Parts Have a Shelf Life?

Silicone polymers themselves do not “expire,” but processing additives do.

Over a period of 5–10 years, plasticizers, flame retardants, or specialty additives may migrate to the surface—a phenomenon known as blooming.

While blooming does not necessarily indicate failure, it can alter:

- Surface energy

- Friction coefficients

- Automated assembly performance

Why Post-Curing Determines Silicone Longevity

Silicone behaves more like a semi-inorganic material than a conventional rubber. Its long-term stability depends less on raw polymer chemistry and more on thermal history during manufacturing.

If residual volatiles are not fully removed through controlled post-curing, the material’s inherent stability is compromised before the part ever enters service.

Key Takeaways

- Silicone does not fail visibly—it fails functionally

- Thermal stability depends on process control, not just Si-O bonds

- Residual volatiles are a primary driver of long-term degradation

- Post-curing is not optional; it defines field performance

- Compression set, hardness drift, and hydrolysis are the true boundary conditions

Silicone stability is not guaranteed by material selection alone. It is engineered—or lost—during manufacturing.