Most teams come to this question expecting a hierarchy.

Medical-grade sounds “higher,” so they assume it covers food contact by default. That assumption causes more rework than almost anything else we see around silicone selection.

Food-grade and medical-grade silicone are not steps on the same ladder. They sit on different regulatory axes, and the gap between them shows up only after parts have been molded, post-processed, and actually used.

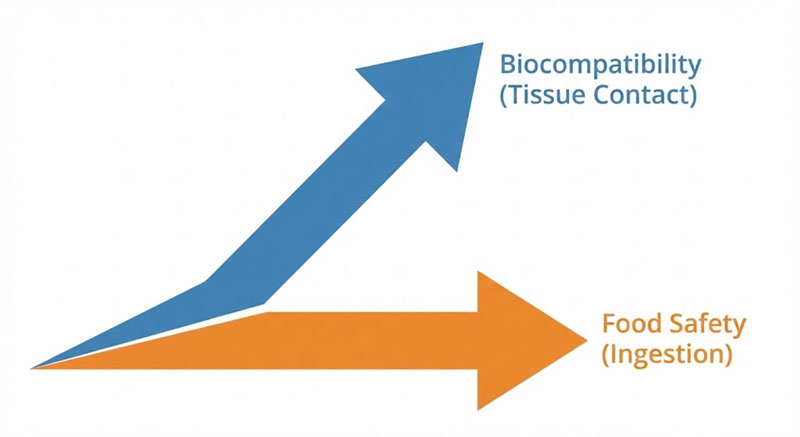

Where the standards don’t overlap

Food-grade silicone is scoped around ingestion risk.

Medical-grade silicone is scoped around biological response.

That sounds abstract, but in production it becomes very concrete.

Food-contact standards focus on:

- Extractables migrating into food simulants

- Taste, odor, and visible residue

- Short, repeated contact at moderate temperatures

Medical standards focus on:

- Cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation

- Tissue contact, sometimes long-term

- Cleanliness and traceability through processing

What’s missing is intentional overlap. A compound can pass food-contact migration limits and still fail biological reactivity tests. The reverse is also true.

This is why “medical-grade is safer” is an unreliable shortcut.

Why medical-grade often fails food-contact expectations

In early discussions, buyers assume medical-grade silicone will automatically be acceptable for food contact. The surprise comes later, usually after pilot builds.

Here’s what shows up in practice:

- Medical-grade formulations often prioritize biostability, not taste neutrality

- Some pigments and additives allowed in medical applications are irrelevant—or problematic—for food

- Post-cure profiles optimized for implant or skin contact don’t always eliminate volatiles that affect odor

On the production floor, this shows up as:

- “Clean” parts that still smell after heat aging

- Taste transfer complaints in soft foods or oils

- Additional post-bake cycles that weren’t planned or costed

Teams underestimate this because medical testing feels more “serious.”

But seriousness doesn’t mean coverage.

Why food-grade often fails medical assumptions

The opposite mistake is quieter but riskier.

Food-grade silicone is optimized to not contaminate what touches it.

That’s not the same as being benign to the body.

Common gaps:

- No testing for long-term skin contact

- No sensitization or irritation data

- Inconsistent traceability at the batch level

In manufacturing terms:

- Raw material substitutions may be allowed without notification

- Cure systems are chosen for throughput, not biological stability

- Regrind policies are looser

For consumer kitchenware, this is fine.

For wearables, feeding accessories, or anything crossing into repeated body contact, it’s not.

The real divider: use context, not grade name

When we evaluate silicone internally, we don’t start with “food vs medical.”

We start with three questions:

- What touches the silicone? Food, skin, mucosa, tissue — each changes the acceptable risk model.

- How long, and how often? Single-use contact behaves very differently from daily, heated reuse.

- What happens after molding? Post-cure time, washing media, storage conditions, and aging all matter more than the label on the compound.

A medical-grade compound that never touches tissue may be unnecessary.

A food-grade compound used in repeated skin contact may be insufficient.

The “grade” doesn’t answer those questions. Process behavior does.

Where teams commonly misjudge this decision

Most misjudgments happen early, for two reasons:

- Procurement collapses standards into a checkbox “Medical” becomes a proxy for safety, without mapping actual contact conditions.

- Design assumes certification is static In reality, compound formulation, post-cure discipline, and even mold release choices shift compliance over time.

These gaps only show up after tooling is cut and validation starts. By then, changing material grade is expensive.

The boundary most people miss

Food-grade and medical-grade silicone are not substitutes for each other.

They are responses to different risk questions.

If your product sits near the boundary—feeding devices, wearables, reusable food tools with heat and skin contact—the correct answer is often dual evaluation, not a single “higher” grade.

That costs more upfront.

It costs far less than discovering, six months in, that the wrong standard was never designed to answer your real risk.